The Theosophical Society in China

Not much information is found in the annals of The Theosophical Society regarding Theosophy in China, save a brief statement in A Short History of The Theosophical Society by Mrs. Josephine Ransom in the Year 1922.

“The first Chinese Lodge had been formed, with the great Chinese statesman and ambassador, Dr. Wu Ting-Fang, as President, but who passed away in June. He was intensely anxious that Theosophy should take root in his own land, for he wished the new China to be built up on the basis of brotherhood.”

In the The Golden Book of The Theosophical Society by C. Jinarājadāsa, there was a picture in Fig. 204 with the caption “Dr. Wu Ting Fang, Author of the first Chinese Manual on Theosophy”.

Be that as it may, we know that Charters were granted to a few lodges in China, as follows:

| Lodge Name | Location | Date of Charter |

| The Saturn | Shanghai | 14/1/1920 |

| The Sun | Shanghai | 8/8/1922 |

| Shanghai (ex-Saturn) | Shanghai | 7/2/1923 |

| Hankow | Hankow | 7/7/1923 |

| Hongkong | Hongkong | 7/9/1923 |

| Dawn | Shanghai | 12/11/1924 |

| Blavatsky (Russian) | Shanghai | 7/1/1925 |

| China (ex-Sun) | Shanghai | 7/4/1925 |

| Tientsin (Russian) | Tientsin | 1/6/1925 |

| North China | Tientsin | 24/8/1925 |

| Shanghai (ex-Shanghai) | Shanghai | 9/9/1931 |

Prior to the formation of the first lodge in China, there were members residing in China who were members of the Theosophical Society from other countries. They were the “TS members attached to other Sections”. Dr. Wu Ting Fang was one such member. He joined the Krotona Lodge, Hollywood, California, USA on 23 August 1916. And there was Mr. Hari Prasad Shastri who joined Shantidavada Lodge, Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, India on 16 February 1914. Almost all the lodges were formed by foreigners living in China at that time, with the exception of Sun Lodge. Lodge meetings and activities were conducted in the languages of the expatriates responsible for the lodges.

The very first lodge to receive a charter in China was the initiative of a group from Shanghai that included Dr. Wu Ting Fang who was then Dr. Sun Yat-sen’s Minister of Foreign Affairs. The proposal to form Saturn Lodge came in a letter dated 6 July 1919 from R. Sims, the pro tem Secretary, as follows.

“Some months ago a number of people got together and a group was formed to study

Theosophy.

At the last meeting it was decided that a Lodge be formed and a Charter applied

for. Would you kindly therefore forward an application form of Lodge Charter

provided for that purpose at your earliest convenience. We will start the Lodge

with 14 members, out of which 4 are members of the T.S. of some years standing.

Shanghai is a very materialistic city and we do hope that the Lodge may help to

turn many in the right direction.

I am enclosing seven application forms for fellowship together with Bank Draft for $ G. 19.50.”

The “4 are members of the T.S. of some years standing” was probably referring to some of the members who were then attached to other Sections including Dr. Wu Ting Fang and Professor Hari Prasad Shastri.

This initial application letter was sent in error to Krotona Lodge, Hollywood, California instead of Adyar. This might be due to the fact that Dr. Wu Ting Fang was a member of Krotona Lodge and they got the address from him. The letter was nevertheless forwarded to and received by Adyar on 29 November 1919, some five months later.

A subsequent letter was sent to Adyar dated 20 December 1919 signed by S. Flemons, as the Hon. Secretary, it says:

“It gives me great pleasure to be able to announce that a Theosophical Lodge has been formed in Shanghai, and which is I believe the first Theosophical Lodge in China.

We are somewhat anxious about our Charter and Diplomas, owing to the long delay which was caused by our ignorance in applying to the Krotona Lodge, American Section, instead of to you. We have since received a reply from Mr. Foster Bailey, stating that we should have applied to Adyar, but that he had forwarded our letter and application forms, together with Gold Dollars 17.50 to your goodself. Would you therefore kindly send Charter and Diplomas to my address at your earliest convenience, for which I thank you.

Our previous Honorary Secretary, Bro. R. Sims has gone on home leave and I had the honour of being elected in his stead.

I am pleased to be able to tell you that the Lodge is progressing rapidly and I have some more application forms filled in, which I am holding over until I hear from you. Kindly furnish me with all particulars as regards amount in rupees to be forwarded both on application for membership and annual dues for each member.

I would also be much obliged if you would send me a catalogue of your books for sale.

Kindly place us down as a subscriber to the “Theosophist”, letting me know the

amount of subscription when you write.

We have called ourselves the “Saturn Lodge”, that being the planet under which we came into existence.”

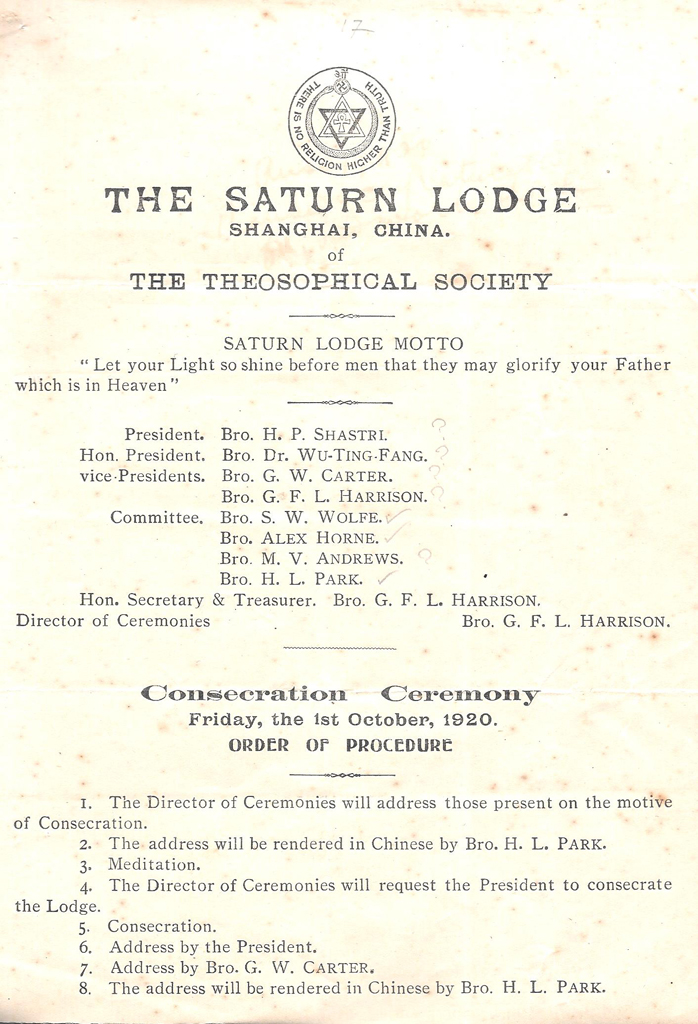

A Charter was issued for the Saturn Lodge and sent together with seven initial diplomas on 14 January 1920. The Saturn Lodge thus became the first Lodge in China to receive a Charter. A duplicate Charter was issued on 8 June 1920 in the names of founding members Capt. & Mrs. George W. Carter, Mrs. Mary E. Lane, Mrs. Rosine Thavanet Williams, Miss M.V. Andrews, Mr. & Mrs. Sims, H. Shastri, S. Flemons, S. Wolfe, Mr. & Mrs. Olsufieff, Miss Shibbeth.

The situation with TS members in China at that time is best described in a letter Rev. Charles Spurgeon Medhurst wrote to Bro. J. R. Aria, then the International Recording Secretary at Adyar. Rev. Medhurst, an early member from America and a missionary in China, wrote in his letter of 20 March 1920 from Peking.

“I should be glad if you would act as a radiating centre for the scattered Theosophists of China. We have no other means of even knowing of each other’s existence except by accident, for we occupy a continent, and are separated by wide distances.

For instance, I see in the Feb. Bulletin a notice of a T. S. Charter being granted to a Lodge newly formed in Shanghai. I should naturally like to be in touch with these new TS members, but have no names and no address. They also do not probably know where I am.

Dr. Wu Ting Fang accidentally found an old Theosophist in Hongkong, of whom he and I knew nothing. I believe also a Mr MacFarlane (Alfred J. MacFarlane), of the L.M.S. (London Mission Society) somewhere in Central China is a Theosophist, but I know little about him.

There may be others. Now, if you would bring us together, mutually introducing us to each other, we might consolidate our forces and and do < > but we cannot unless you will tell us who’s who.

I was glad to receive some time ago a letter from you introducing Prof. Cousins, but unfortunately he did not approach nearer than 300 miles from Peking. I believe however he met Dr. Wu.”

Evidently, Dr. Wu Ting Fang, although he was China’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, was very much active behind the scene at the Saturn Lodge. In a letter dated 17 September 1920 written by G.F.L. Harrison as the Hon. Secretary, he referred to Dr. Wu Ting Fang as the Hon. President. Indeed, in the programme for the Consecration Ceremony on 1 October 1920, Dr. Wu Ting Fang was listed as the Hon. President.

In his letter of 8 October 1920, G.F.L. Harrison reported

On Sunday next, the 10th Oct, we have the first meeting for our Chinese Members, all will be given in Chinese, our Hon. President, Dr. Wu Ting Fang, is to give the inaugural address. I will let you know how we go on and will send you a copy of our Lodge quarterly magazine, when it is published, which will contain a full account thereof.

In his letter of 29 December 1920, G.F.L. Harrison says,

Dr. Wu Ting Fang, our Hon. President, gave a public lecture in Chinese on

Theosophy a few weeks ago. We had an audience of about 500, which marks the

first attempt at propaganda work here among the Chinese and was very successful.

Unfortunately, Dr. Wu has had to leave for Canton and so this work has been

stopped for the time being. When he returns we hope to proceed further. I might

mention that his lecture was printed in all the leading Chinese newspapers of

Shanghai, so those who were not present had the opportunity of reading something

about Theosophy in their own language.

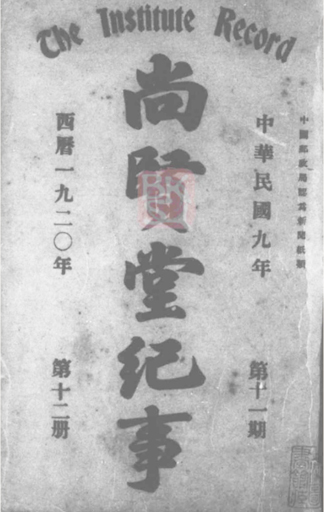

The event was in fact recorded in the chronicles of 尚賢堂 (Shangxiantang – The International Institute of China). The public lecture was given in December 1920 at the New Helen Theatre (新愛倫影戲院) at Haining Road (上海海寧路) according to the report. The subject of the lecture was The Principle of Life and Death (生死之理) and as many as 1,000 were in the audience as reported in the chronicle (尚賢堂紀事).

Chronicle of Shangxiantang, 1920/12

The first Theosophical literature in Chinese was printed in December 1920. This was a 3-page document translated from a Theosophy pamphlet provided by the National Publicity Department, Theosophical Society, Krotona, Hollywood, Los Angeles, California. At that time, the Theosophical Society was known in Chinese as Daodetongshenxue (道德通神學).

Dr. Wu Ting Fang, second row

seated 6th from the left, on his left Prof. H. P. Shastri

(circa 10 September 1920)

But who was Dr. Wu Ting Fang? No further information was given in theosophical publications regarding this Chinese pioneer of Theosophy. Though a distinguished name in China’s modern history, few realize the significance of this name or the extent of his greatness. Wikipedia describes him as “a Chinese diplomat and politician who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs and briefly as Acting Premier during the early years of the Republic of China; a lawyer and a calligrapher”. The Chinese edition of Wikipedia and the Chinese Baidu Encyclopedia give considerably more information on the illustrious background of Dr. Wu Ting Fang. What was not known or not stated was the fact that Dr. Wu was veritably the Father of Theosophy in China.

.jpg)

Wu Ting Fang (伍廷芳) was reportedly born on 30 July 1842, interestingly, in Singapore, which was then known as the Straits Settlements. However, at 3 years of age, he was taken by his father back to China where a greater destiny awaited him. He had his early education in Hong Kong. In 1874 he went on to study Law in England at University College London and was called to the bar at Lincoln’s Inn in 1876. Wu Ting Fang became the first ethnic Chinese barrister in history. It is interesting to note that at the time when The Theosophical Society was founded in New York with its attendant publicity in London, Dr. Wu was in fact living in England. However, it is not known if he had any contact with early members of the Theosophical Society.

After being called to the bar in England, he returned to Hong Kong in 1877 to practise law. Dr. Wu Ting Fang became the first ethnic Chinese Unofficial member of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong when he was appointed by Great Britain in 1880, a position he served until 1882.

Dr. Wu was appointed by the Emperor Guangxu and served under the Qing Dynasty as Minister to the United States, Spain and Peru from 1896 to 1902. He returned to the United States to serve as the Chinese Minister for the United States, Mexico, Peru and Cuba from 1907 to 1909. During this time he became friends with President Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt and also met with the scientist and inventor, Thomas Edison, also a Theosophist. In March 1910, Dr. Wu left the United States for Europe, Singapore and Hong Kong, enroute to Beijing.

During his first term as Imperial Chinese Ambassador to the United States, Wu Ting Fang received an honorary Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) from the University of Pennsylvania. The degree was awarded in 1900, at the height of his fame and popularity in America. He was invited to deliver an address at the university on Washington's birthday, February 22, 1900. The honorary degree was conferred upon him during this visit. His speech was titled "The Proper Relations of the United States to the Orient". In the address, Wu took the opportunity to explain Chinese culture and history to his American audience, a role he often took on during his ambassadorship. His time in the United States made him a very popular figure with Americans, and institutions like the University of Pennsylvania sought to honour him. The degree acknowledged his diplomatic work and his efforts to bridge the cultural gap between China and the U.S. At the ceremony, university officials praised Wu Ting Fang not only as a representative of the Chinese government but also as a "foreign guest" who was being honoured for his "striking example of the friendly feeling shown to the country which I have the honour to represent".

Wu Ting Fang was awarded his second honorary Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) degree by the University of Chicago in 1901. At the time, he was the Imperial Chinese Minister (ambassador) to the United States. His visit to Chicago and the university garnered significant attention from the press. On March 19, 1901, Wu Ting Fang delivered the convocation address at the university's Studebaker Theatre. His address focused on Chinese Civilization, in which he argued that his nation's civilization was no less sophisticated than Western cultures, despite being different. His visit and speech were covered by major newspapers, including The New York Times, with headlines like "Minister Wu in Chicago". During his three-day stay in Chicago, the university hosted receptions and dinners in his honour. He was a popular public figure known for his charisma and wit, which drew large crowds. While the University of Chicago has since developed a policy of not giving honorary degrees to diplomats unless they meet stringent academic requirements, Wu Ting Fang was recognized at a time when such awards were more common for prominent figures. The award recognized his legal accomplishments, particularly his pioneering work as the first ethnic Chinese lawyer to be called to the bar in England.

Wu Ting Fang received his third honorary degree from the University of Illinois in 1908. During his second term as Chinese Minister to the United States (1907–1909), he was invited to deliver the commencement address at the university on June 10, 1908. Wu Ting Fang’s commencement address was titled "Why China and America Should Be Friends," in which he emphasized the importance of mutual respect between the two nations. Newspaper accounts describe the grand impression he made at the ceremony and the thunderous ovations he received both when UI President Edmund J. James introduced him and after he concluded his speech. The speech itself was very well received. Emphasizing the importance of the two nations gaining a respect for each other, he said, “This mutual interchange of ideas and ideals and the adoption of the one of what is best and highest in the other will result in the birth of a new civilization, the civilization of the Pacific Ocean… Another chapter will be added to the history of civilization, a chapter in which the east and west, laying aside all feelings of antagonism and prejudice will vie with each other not in the achievements of might, but in the victories of peace, aggressive only in the dissemination of truth and light and relentless only in the establishment of justice and right.”

The honorary Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) degree was conferred upon him during his visit, acknowledging his diplomatic work and his role in fostering a positive relationship between China and the U.S. He was also pictured with Chinese students on the campus, highlighting his engagement with the academic and diplomatic exchange programs that were growing at the time. Wu Ting Fang’s visit was a significant event for the university, occurring during a period of growing popularity for Chinese students at the school. It helped solidify the University of Illinois's strong ties with China, which included appointing one of the first advisors for foreign students in the country.

Wu Ting Fang was well-known as a Chinese diplomat in the U.S. for his charm, wit, and unique ability to bridge cultural divides during a critical time for US-China relations. He was a celebrated figure who attracted significant media attention and public interest for his unconventional and insightful style. Having received a blended education in mainland China and Hong Kong, Wu Ting Fang spoke fluent English and was a trained lawyer from Lincoln's Inn in London. This made him China's first English-speaking minister to the U.S. and allowed him to communicate directly with American officials and the public. He was able to explain Chinese culture and traditions to Western audiences in a relatable way, challenging prevailing stereotypes and misunderstandings. He was famed for his wit and candour. He was a popular speaker at universities, forums, and social gatherings, where he would engage and amuse his audience. He regularly gave interviews to the American press, but was known to cleverly turn the tables and end up interviewing the reporter himself.

Wu Ting Fang’s posting occurred at a crucial time for China, when its very survival as a state was in question. His diplomacy was instrumental in cultivating a bilateral relationship with the U.S. to ensure his country's survival. He strongly advocated for the rights of Chinese immigrants in the U.S. and protested against anti-Chinese measures.

Dr. Wu Ting Fang resided in the West for a considerable period of time, some four years in England and eight years in the United States. His mastery of the English Language and his knowledge of the current affairs worldwide could be seen from the delightful book he authored, America Through the Spectacles of an Oriental Diplomat. This book is immensely readable. Interestingly, he was coaxed to write this, his only English book, by an American lady friend as it says in the Preface:

“Such a race should certainly be very interesting to study. During my two missions to America where I resided nearly eight years, repeated requests were made that I should write my observations and impressions of America. I did not feel justified in doing so for several reasons: first, I could not find time for such a task amidst my official duties; secondly, although I had been travelling through many sections of the country, and had come in contact officially and socially with many classes of people, still there might be some features of the country and some traits of the people which had escaped my attention; and thirdly, though I had seen much in America to arouse my admiration, I felt that here and there, there was room for improvement, and to be compelled to criticize people who had been generous, courteous, and kind was something I did not wish to do. In answer to my scruples I was told that I was not expected to write about America in a partial or unfair manner, but to state impressions of the land just as I had found it. A lady friend, for whose opinion I have the highest respect, said in effect, “We want you to write about our country and to speak of our people in an impartial and candid way; we do not want you to bestow praise where it is undeserved; and when you find anything deserving of criticism or condemnation you should not hesitate to mention it, for we like our faults to be pointed out that we may reform.” I admit the soundness of my friend’s argument. It shows the broad-mindedness and magnanimity of the American people. In writing the following pages I have uniformly followed the principles laid down by my American lady friend. I have not scrupled to frankly and freely express my views, but I hope not in any carping spirit; and I trust American readers will forgive me if they find some opinions they cannot endorse. I assure them they were not formed hastily or unkindly. Indeed, I should not be a sincere friend were I to picture their country as a perfect paradise, or were I to gloss over what seem to me to be their defects.”

This delectable book is witty, humorous, if sometimes satirical, but written with great humility. It was written in 1914 when Dr. Wu Ting Fang had taken up important portfolios in the new Republic of China.

We are most grateful to Chuang Chienhui (莊千慧) for the information she provided in Chapter 4 of Theosophy across Boundaries [edited by Hans Martin Krämer & Julian Strube and published by the State University of New York Press. (2020)], on Theosophical Movements in Modern China which we have quoted copiously below.

Dr. Wu Ting Fang finished his mission as the Qing Dynasty Minister to the United States, and returned to China in 1910. When he returned, he immediately resigned because of his dislike for the political corruption prevalent among the Qing. He moved to Shanghai and became engulfed in studying Theosophy. A report says that in 1910, Wu took a break from work. Also, Wu hoped to “gather Western and Chinese intellectuals who live in Shanghai together for the establishment of a Theosophical Society and carry on research on the essence of religions such as Confucianism, Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam.”

It would be noted that Dr. Wu Ting Fang officially joined the Theosophical Society as a member of the Krotona Lodge, Hollywood, California on 23 August 1916, although it was reported in the press that on 12 March 1916 Dr. Wu, in his capacity as a Theosophist, was invited by the Shanghai Shangxian Tang (上海尚賢堂 The International Institute of China) to give a talk to an audience of hundreds of people.

Apparently, Dr. Wu began his propaganda work for Theosophy in China from the 1910s. During the 1910s, his Theosophical propaganda was related to three Western Baptists: Timothy Richard, Gilbert Reid, and C. Spurgeon Medhurst. Timothy Richard and Gilbert Reid were not Theosophists, but all three figures had similar views regarding the religions of East and West. Medhurst, who originally came to China as a Baptist missionary, joined the Theosophical Society in America on 19 October 1896 and he should also be considered a pioneer of the Theosophical Movement in China. Spurgeon Medhurst was forced to resign his clerical post in 1904 owing to his involvement with the Theosophical Society. The International Theosophical Yearbook first recorded Spurgeon Medhurst’s Theosophical Movement in China in 1909.

Dr Wu presented a paper about Chinese Civilization at the “First Universal Races Congress” in July 1911, where Annie Besant was on the list of sponsors and accompanied by Gandhi. At this congress in London, Dr. Wu remarked that he preferred Chinese civilization. He explained the concept of Chinese civilization using words from the Confucian classics: “We should treat all who are within the four seas as our brothers and sisters.” This point of view may be associated with the first object of the Theosophical Society, namely the doctrine of “universal brotherhood.” Wu’s paper was also reported by The Theosophist in October 1911. Dr. Wu later stated that he began to study morality and religion after the success of the Xinhai Revolution, which took place from 1911 to 1912.

In Shanghai in 1912, Timothy Richard, Gilbert Reid, and Spurgeon Medhurst founded a research society for discussing “world religions” (Shijie zongjiao hui), focusing on the study of comparative religion. In 1913, Spurgeon Medhurst, who had previously published a translation of the Taoist classic Dao de jing through the Theosophical Society, gave a speech at Gilbert Reid’s International Institute of China (Shang xiantang) in Shanghai. He spoke of “the great spontaneity or Natural Law of the universe,” “purity,” finding “satisfaction in service for others,” “worldwide unity,” and “life eternal or immortality” as the five “hopes” in Laozi’s teaching, which may remind the reader of similar doctrines in Theosophy. The first record of Dr. Wu and Medhurst’s cooperation for Theosophical propaganda dates from January 1916. Meanwhile, the influential Chinese-language newspaper Shen Pao reported that Dr. Wu and Spurgeon Medhurst had founded a society for the research of religion in Shanghai. Lectures and speeches held at the International Institute of China were open to people of all nationalities, and local journalists often wrote about them in Chinese and English newspapers.

Starting in January 1916, Wu and Medhurst delivered speeches about Theosophy at the International Institute of China in Shanghai. In March the same year, The Shanghai Times posted an announcement about an upcoming lecture by Wu. It said that Wu would talk about “another subject in Theosophy” under the title of “The Human Soul in Its Relation to the Physical Body and Its Consequences.” The progress of the lecture was described in one of Chinese magazines for young students as follows:

Wu Ting Fang of the Tongshen Society was invited to the International Institute of China to deliver a lecture on the relation between the soul and the body. There were hundreds of people who came to see his speech. According to Wu’s words, the human soul will never die. There is no beginning nor ending in it. [. . .] The human body is like clothes, it’s not good to consider it too important. If we don’t train ourselves well, we cannot evolve. If we train ourselves well over and over, we will change, becoming perfectly good men, and will arrive at a state of bliss. [. . .] Things which have shapes are yang, those without shapes are yin. Yin comes first, and then yang comes afterwards. People know of earthly matters but don’t know that there are numerous worlds besides the earth. The qi of individuals, the air of emotions, does not occur only within us. It may be felt by others. [. . .] There is a book written by a Westerner, which has collected pictures of qi taken with a camera. Many kinds of photos are included, please take a look. (Wu opened the book and showed every page to his audience. There are about 50 pages in the book.) People’s goodness and badness are classified according to shapes and colors.

Wu’s use of terms such as ying, yang, and qi in his lecture suggests that he combined Theosophy with Daoism when he introduced Theosophy to the Chinese. The “book by a Westerner” that he showed as evidence to the audience is, in all likelihood, C. W. Leadbeater and Annie Besant’s Thought-Forms; nevertheless, he did not mention the authors’ name, or the Theosophical Society, in the lecture. Furthermore, Wu showed his collections of Western spirit photography to those in attendance to make them believe in the existence of life after death. The only thing he did not mention is what Theosophy was. Gradually, Wu and Medhurst’s efforts came to be noticed by the Chinese. In 1916, the education department of Jiangsu Province invited Wu to give a speech about Theosophy as a member of the Tongshen Society (Tongshen hui). Tongshen is the Chinese translation of Theosophy, which means “connected with God.” This lecture was reported not only in a bulletin of the Jiangsu province’s education department, but also in other Chinese newspapers and magazines. Wu stated that Western science had created doubt about the existence of spiritual matters both in the East and in the West. As for China, in the Confucian classic The Analects of Confucius, it is written: “Confucius does not speak about occult violence and spiritual matters,” and “How can you know death when you still don’t know about life?” Although Confucius did not deny life after death, research into spiritual matters had not been appreciated in the Confucian tradition. A friend of Wu’s living in Beijing read Wu’s Theosophical lecture in a newspaper and sent him a letter asking what the soul (linghun) was. Wu’s friend said his view was ridiculous and inappropriate for the modernized world. Wu used his friend’s question as an introduction to his talk at the educational department of Jiangsu province.

I replied to him that this is a profound theory which can’t be explained in a letter. If you don’t believe in ghosts (gui), may I ask you whether you worship your ancestors? Doesn’t ancestor worship show a belief in the existence of ghosts? Our Confucius said, “The ghosts’ function in morality is huge.” Isn’t this evidence that the Saint believed in the existence of spirits? As for those who don’t believe in it, it is because they know less, so they think it strange. If they study it, then they must suddenly achieve a total understanding. No religion denies the existence of the soul (linghun).

Wu’s lectures about soul were also related with his friends in the International Institute of China. The International Institute of China, the first place where Wu and Medhurst delivered speeches about Theosophy, was established by Gilbert Reid. It was also known as a place for the improvement of cultural exchange and the introduction of different kinds of religions and philosophy. Timothy Richard published a book in 1910 titled The New Testament of Higher Buddhism. The North-China Herald (Beihua jiebao), an influential English-language newspaper in Shanghai, introduced Richard’s new book soon after its publication in the following way:

The general reader and even these students in the West who are now studying Buddhism are left in a confused state of mind as to its real place among the religions of the world, owing to Theosophy, and Edwin Arnold’s Light of Asia, which was written at a time when the true relation of Higher and Lower Buddhism was not known. This book contains two most important translations—one, the origin of Higher Buddhism called “The Awakening of Faith,” and the other, “The Essence of the Lotus Scripture.” The first was translated into English before, but by one unacquainted with Buddhist key to the central thought of the True Model Chin Ju. The second has never been translated before, though the Lotus of the Good Law was translated in the Sacred Books of the East. No student of Higher Buddhism should be without this book.

Even though Timothy Richard’s Buddhist translations were influenced by his Christian cultural background, his views of Eastern religions, unlike those of other Western Baptist missionaries who despised them, were characterized by his seeking communality between Eastern and Western religions. Judith C. Powles points out that even after Medhurst resigned his missionary post, his “nearest friend,” Timothy Richard, maintained his connection with him. We may say that Medhurst and Wu’s Theosophical movement in the China of the 1910s flourished because of the support of their considerate Christian missionary friends in China. However, their cooperation did not occur simply because of friendship, but as part of a wave of reconsideration of the religious concepts in the 1910s. In addition, Richard, Reid, Medhurst, and Wu were also associated with the Mahayana Association in Japan in 1916. Although the Mahayana Association was not directly connected to the Theosophical Society, many Western members of the association were Theosophists. Theosophy was the impetus that made Christian Baptists such as Timothy Richard translate Buddhist classics through a Christian filter but at the same time seek uniformity. Medhurst’s translation of the Dao de jing may be taken as providing a means for illustrating the commonalities between Eastern and Western wisdom. Wu Ting Fang tried to encourage the practice of Theosophy as providing a means for the settling of conflicts regarding nations, races, religions, and so on worldwide. Theosophy would play the role of catalyst for the rethinking of religion and also as mediator between Eastern and Western thought systems.

In August 1916, the Theosophical magazine, Reincarnation, wrote about Wu’s and Medhurst’s Theosophical movement as follows: “It is a pleasure to note that the Legion work has been satisfactorily started in Shanghai, China, where there are now six members and an active Group will probably soon be chartered. Among the members are the well- known names of Wu Tingfang, former Chinese minister to the United States, and Rev. C. Spurgeon.” Then, in November of that year, the magazine of the Theosophical Society in Adyar, The Theosophist, reported that Wu and Medhurst were forming a Theosophical study circle (The Theosophist 38 [1916]: 122)

Wu and Medhurst made great efforts in disseminating Theosophical propaganda and forming a Theosophical study group in 1916. However, Wu joined the Constitutional Protection Movement in 1917 and came to be the temporary premier of the Republic of China from May to June, then took on the post as Foreign Minister from September, which meant that he could not stay in Shanghai. Medhurst established the Quest Society in Shanghai, which held lectures on various subjects from religion to alchemy. In 1918, several Theosophists in Shanghai participated in Quest Society events and initiated a “study circle” for Theosophy soon after that. Through these movements in the 1910s, Captain George W. Carter and Hari Prasad Shastri established the first official Theosophical lodge in China, the Saturn Lodge, in the Shanghai French Concession. It had thirteen members in the beginning and came to have twenty- eight members after one year. Hari Prasad Shastri, a professor, Sanskrit scholar, and Raja Yoga teacher, was its first president. Chinese members held a study circle and gave Chinese-language lectures about Theosophy every Sunday. Though he was extremely busy during the Chinese Civil War, he still provided support to the running of the Saturn Lodge. The Saturn Lodge did not have a regular meeting site in its first year. At first, members’ residences, such as that of George Carter, as well as Wu’s, were used in the summer. One year later, Dr. Wu was elected as honorary president in 1920.

Though Wu was busy at the time, he organized a new lodge in Shanghai in 1922, the Sun Lodge, which was the first lodge run by Chinese natives. Moreover, he pioneered Chinese Theosophical literature with his “Wu Tingfang’s theory of soul,” the first Chinese-language Theosophical Manual. Wu stayed in South China as part of the Constitutional Government in Canton under Sun Yat-sen, holding the position of Minister of Finance. Cen Chunxuan, the leader of the military government in Canton, forced Wu to hand over the funds for a forthcoming university’s establishment in China. Cen wanted to use the funds for his army, so Wu decided to leave Canton with the money in March 1920 and hide in Hong Kong. There he met James H. Cousins, an Irish poet and an active Theosophist. Wu told Cousins that he wanted to help the Theosophical movement and do “all he can in China.” Wu offered to send Cousins on a lecture tour of China with his financial support, which would amount to 2,000 rupees. Wu was on his way to Shanghai during this period to escape from threats against him. Wu and Cousins planned to start further propaganda on behalf of the Theosophical Society after political circumstances improved. However, their plan could not be realized because Wu died in June 1922.

In 1921, Spurgeon Medhurst and his wife left Shanghai for Sydney to visit C. W. Leadbeater. He was to live in Australia until his death. Wu and Medhurst’s work had significantly facilitated the early Theosophical movement in modern China; however, the progress of the movement declined after Wu Ting Fang’s death in 1922.

In the 1910s, Wu emphasized the importance of making the Chinese believe in the existence of life after death. He also emphasized that research on life after death is not superstitious, nor should it be marginalized. He used Confucian and Daoist sayings as a way in, and his collections of Western spiritual photography as evidence. Before introducing the notion of Theosophy, he had to explain the idea of life after death. His Chinese lectures about Theosophy during the 1910s only briefly mentioned what Theosophy and the Theosophical Society were. His first detailed introduction about H. P. Blavatsky and the Theosophical Society was in his first Chinese-language Theosophical manual, published in 1921. The reason might be explained by his conversation with the Indian scholar Benoy Kumar Sarkar in 1916, in which Wu asked Sarkar if he knew about Theosophy:

Wu laughed and said, “Right. These days I’m thinking of

visiting Madras when the war is over.” When Sarkar enquired if the visit to

Madras would be a “pilgrimage,” Wu laugh and said, “Right. These days I’m

studying (the concepts of) soul, the world beyond death, rebirth, etc. I’ve

given up eating fish and meat. It’s my desire to lead a solitary life on a

mountain following the ideals of your Buddha.” Wu also told Sarkar that he had

started a movement among the Chinese youth to reform their eating habits by

becoming vegetarians. To promote this movement, he opened a restaurant that

served only vegetarian food. “But the customers were limited,” the old diplomat

told him, “then one night some miscreants set fire to the restaurant . . . and

that’s why I am very disheartened.” Using his personal loss as a metaphor for

the political uncertainties in China, Wu remarks, “After all, in every reform

movement in the world the pioneers or the pathfinders experience such maladies.”

According to this conversation, Wu’s concern with Theosophy started from his interest in spirituality, and his Theosophical movement may be defined as a movement for progress and social reform. After Wu returned to China in 1910, he immediately established a society for vegetarianism (Shenshi weisheng hui). Then the next year he attended the “First Universal Races Congress” in London and declared his ideal of Chinese Civilization. In his English book America: Through the Spectacles of an Oriental Diplomat (1914), Wu mentioned Annie Besant’s support as far as two of his ideas were concerned: the citizenship of immigrants and the benefits of vegetarianism. It was rightfully pointed out, the similarities between Wu’s political ideas and his Theosophical literature: indeed, Wu’s objection to enacting Confucianism as the only Chinese state religion was based on the Theosophical aim of “universal brotherhood.” Interestingly, Dr. Wu Ting Fang wrote the Introduction to Benoy Kumar Sarkar’s book, Chinese Religion Through Hindu Eyes, that was published in March 1916. It was thus acknowledged:

Dr. Wu Ting-fang, LL.D., late Chinese Minister to Washington, D.C. (U.S.A.), has kindly contributed his ideas on the Religion of the Chinese in the form of an Introduction to this work. The author is grateful for the favour thus accorded him by the veteran Confucianist scholar.

Indeed, with his mastery of the English language Dr. Wu introduced Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism with great clarity and unambiguously. And, by the by, he also mentioned Muhammadanism and Christianity for good measure, on religions in China, in his 12-page Introduction.

Around 1918, Chinese intellectuals were working on psychical research in Shanghai to prove the existence of life after death. Many well-known intellectuals were engaged in psychical research to introduce it as a new science in the West. Wu Ting Fang’s view of the soul was used in support of their theory. Their work was a fusion of psychical research and traditional religious rites. Their research was severely criticized for being based on superstition by members of the New Culture Movement, which criticized traditional values and advocated Western civilization. This made people steer clear of spiritual issues and religions. Those audiences who listened to Wu’s Theosophical speeches during the 1910s might have obtained the impression that Theosophy was similar to Spiritualism.

In 1912, the Republic of China was established. Then World War I began in Europe. Chinese intellectuals in the 1910s focused on conflicts between the “old” and “new.” They tried to understand what kind of civilization their country needed. In this way, they were enthusiastic about finding solutions for what they regarded as two problems in China: moral bankruptcy and loss of spiritual faith. These attempts to define Chinese culture were intertwined with the aim to renegotiate the meaning of religions and philosophies. Against this historical background, Wu not only added “moral” to the Theosophical Society’s Chinese name but also expounded on the existence of life after death. He encouraged the Chinese to conduct research on all kind of religions and philosophies from across the world. Wu’s Theosophical propaganda fit the Zeitgeist. Under his leadership, the Theosophical movement conducted research on spirituality, social reform, and anti-colonialist movements. However, since then, the Chinese have considered these activities separately instead of understanding them as parts of the Theosophical movement. Wu Ting Fang was one of the pioneers of Spiritualism and vegetarianism in China and was admired for his efforts in gaining equal rights for Chinese immigrants. Because these achievements were based on the aims of the Theosophical Society, the Theosophical impact in modern China should be reassessed.

On the other hand, the unique Theosophical education that the Theosophists aimed to practice failed mainly because of the situation brought about by the rise of Western and Japanese imperialism in China. The Theosophical Society’s aim of “universal brotherhood” was a key feature of Theosophical propaganda in China. From the 1910s to the early 1920s, Wu’s Theosophical propaganda presented Theosophy, and in particular its internationalist aspects, as an effective theory for Chinese social improvement and as a tool to negotiate cultural conflicts between the East and West in China. Moreover, with the intensification of Western and Japanese imperialism in China, the needs for social improvement changed into a need for national salvation. The educational rights movement and the anti-Christian demonstrations held from the mid-1920s in China were both related to anti-colonialism. The Chinese did not resist Christianity because of anti-religious sentiments; rather, wariness of being culturally colonialized by Christian missionaries was the more important causal factor for those demonstrations. Moreover, the fusion of Eastern and Western thought by foreigners was perceived as dangerous by the Chinese people for the same reason. It was difficult for the Chinese to perceive the difference between “universal brotherhood” and Western cultural colonialism. However, although the Theosophical educational movement and Wu’s Theosophical literature have been forgotten by the Chinese, the Chinese Theosophists who participated in its educational movement worked actively in the Chinese educational world. Furthermore, those activities of Wu’s Theosophical propaganda, such as human rights and vegetarianism, are remembered by people in Greater China and continue to be practiced as social reform movements even today.

Dr. Wu supported the Xinhai Revolution and negotiated on the revolutionaries’ behalf in Shanghai. He served briefly in early 1912 as Minister of Justice for the Nanjing Provisional Government, where he argued strongly for an independent judiciary, based on his experience studying law and travelling overseas. After this brief posting, Dr. Wu became Minister of Foreign Affairs for the ROC.

Dr. Wu joined Dr. Sun Yat-sen’s Constitutional Protection Movement and became a member of its governing committee. He advised Dr. Sun against becoming the “extraordinary president” but stuck with Dr. Sun after the election. He then served as Dr. Sun’s foreign minister and as acting president when Dr. Sun was absent. He served briefly in 1917 as Acting Premier of the Republic of China. He was the Minister of Foreign Affairs from September 1917 to June 1922 and also concurrently as the Minister of Finance from May 1921 to June 1922. He died shortly after Chen Jiongming rebelled against Dr. Sun.

It was during the last three years of his life that he did the most work for the Theosophical Society while still holding the dual portfolios of Minister of Foreign Affairs and Minister of Finance. In 1920, aged 78, while residing in Shenjiang, Shanghai, he actively promoted The Theosophical Society. He initially named Theosophy Daodetongshenxue (道德通神學) and renamed it Tianrenmingdaoxue (天人明道學) before finalizing on the name Zhengdaoxue (證道學). The choice of the final Chinese name for the Theosophical Society was explained as follows:

道德通神會改名證道學會之原因

此會名由英文翻譯其英文係 Theosophical Society 按照原文字意。是 “神智會”。查近日所刊英華字典。譯解 “通神會”。 惟恐閱者未知內容。疑本會與鬼神通處。誤為旁門左道。故添道德二字。表明宗旨正大耳。近仍有西士函評通神二字尚未妥當。請斟酌再改。是以與友人研究討論。再定名證道學會。其理由詳述於下。僅按世界宗教。其原皆出於天。其所研究主張之理。即天與人關係之理也。若泛言天道。而忽略人事。或徒論人事而蔑視天道。均不能以天道管攝人事。及以人事證明天道。繁言冗說。終是不明。不明即不通。欲恃此化導眾生。甚難覺悟。故談天道者必須有統系。有證據。以科學之條理。求大道之指歸。切於人事。當於人心。使人易知易明。不使人迷惑失據。天道人事。一以貫之。到此境界。謂之天道人道。均無不可。惟此種道理。經數千年宗教家道德家反覆陳說。尚苦其未明。故中國漢代儒家董仲舒云。 “天人之際。甚難明也。” 即指此理而言。今將神人死生及靈魂肉體種種未易說明之道。求所以明之。故定名為證道學會。

Every Thursday Dr. Wu would invite Chinese and Western members to get together at his house to study the true teachings of the various religions, the deep mystery and secrets of heaven and earth (Nature), man’s constitution, etc., in short, Theosophy. According to his followers, whenever he had any leisure after his official duties, Dr. Wu would enthusiastically talk to the Chinese and Western members on Theosophy and occult science and teachings.

Evidently, Dr. Wu gave public talks on theosophy long before the first Chinese Lodge was officially chartered. It was reported in the press that on 12 March 1916 Dr. Wu, in his capacity as a Theosophist, was invited by the Shanghai Shangxian Tang (上海尚賢堂 The International Institute of China) to give a talk on “The Relationship Between the Soul and the Body” to an audience of hundreds of people.

三月十二日四時。上海尚賢堂請通神社伍廷芳君演說人之靈魂與身體之關係,到者數百人。(《伍廷芳演說靈魂》,《教育週報》(杭州),第124期,1916年)

In June 1921, Dr. Wu Ting Fang translated and published Information for Enquirers (證道學指南) by Annie Besant. In July 1921, he wrote and published Outline of Theosophy (證道學會要旨). In the latter publication he gave the reasons with an insightful explanation of the choice of the final name Zhengdaoxue (證道學). It should be noted at this time Dr. Wu Ting Fang was concurrently both the Minister of Foreign Affairs and the Minister of Finance. On 14 February 1922, Dr. Wu published Elementary Lessons on Karma (因果淺義) which he translated from Annie Besant’s writing. The latter was published four months before his death on 23 June 1922.

On 8 March 1923, the Shenjiang Theosophical Society Sun Lodge (申江證道學會太陽會所) posthumously published Dr Wu Ting Fang’s Dialogues On Theosophy (伍廷芳證道學説). These dialogues were recorded answers by Dr. Wu to questions on Theosophy. In the Preface to this book, tribute was paid to Dr. Wu Ting Fang “as a great sage of the Republic of China who led a life with careful words and deeds, and who did not seek luxury. Everything he did was based on morality as the yardstick.” This book was published together with a compilation of the three other works of Dr. Wu, viz. Outline of Theosophy, Elementary Lessons on Karma and Information for Enquirers. This compilation of Dr. Wu’s works on Theosophy can be found in the archives of the National Library of China although the last two titles appear to be missing.

Dr. Wu Ting Fang lived in the era of the founding of The Theosophical Society and the first half a century of its existence. He was a contemporary of the early leaders of the Society. It is not known whether he has ever met any of them but evidently he had great admiration for the leaders such as Annie Besant who incidentally was five years younger than Dr. Wu. In America Through the Spectacles of an Oriental Diplomat, published in 1914, he referred to Annie Besant more than once.

“The immigration laws in force in Australia are, I am informed, even more strict and more severe than those in the United States. They amount to almost total prohibition; for they are directed not only against Chinese laborers but are so operated that the Chinese merchant and student are also practically refused admission. In the course of a lecture delivered in England by Mrs. Annie Besant in 1912 on ‘The citizenship of colored races in the British Empire’, while condemning the race prejudices of her own people, she brought out a fact which will be interesting to my readers, especially to the Australians. She says, ‘In Australia a very curious change is taking place. Color has very much deepened in that clime, and the Australian has become very yellow; so that it becomes a problem whether, after a time, the people would be allowed to live in their own country. The white people are far more colored than are some Indians.’ In the face of this plain fact is it not time, for their own sake, that the Australians should drop their cry against yellow people and induce their Parliament to abolish, or at least to modify, their immigration laws with regard to the yellow race?”

Dr. Wu Ting Fang was also an advocate of vegetarianism. In the concluding chapter of the same book, Chapter 17 on Sports, he writes:

“As an ardent believer in the natural, healthy and compassionate life I was interested to find in the Encyclopaedia Britannica how frequently vegetarians have been winners in athletic sports. They won the Berlin to Dresden walking match, a distance of 125 miles, the Carwardine Cup (100 miles) and Dibble Shield (6 hours) cycling races (1901-02), the amateur championship of England in tennis (four successive years up to 1902) and racquets (1902), the cycling championship of India (three years), half-mile running championship of Scotland (1896), world’s amateur cycle records for all times from four hours to thirteen hours (1902), 100 miles championship Yorkshire Road Club (1899, 1901), tennis gold medal (five times). I have not access to later statistics on this subject but I know that it is the reverse of truth to say, as Professor Gautier, of the Sarbonne, a Catholic foundation in Paris, recently said, that vegetarians ‘suffer from lack of energy and weakened will power.’ The above facts disprove it, and as against Prof. Gautier, I quote Dr. J. H. Kellogg, the eminent physician and Superintendent of Battle Creek Sanitarium in Michigan, U.S.A., who has been a strict vegetarian for many years and who, though over sixty years of age, is as strong and vigorous as a man of forty; he told me that he worked sixteen hours daily without the least fatigue. Mrs. Annie Besant, President of the Theosophical Society, is another example. I am credibly informed that she has been a vegetarian for at least thirty-five years and that it is doubtful if any flesh-eater who is sixty-five can equal her in energy. Whatever else vegetarians may lack they are not lacking in powers of endurance.”

Here again, Annie Besant is mentioned.

Indeed, on 13 May 1922, Dr. Wu Ting Fang wrote a letter to Annie Besant from Canton:

Dear Madam,

Hearing you are paying a visit to Sydney, the officials of the Saturn Lodge at

Shanghai in which I heartily join extend to you a cordial invitation to come to

Shanghai. The Lodge has been established for several years and is doing very.

The members naturally wish to have the President come to their Lodge and address

them.

When you decide to come to Shanghai which I hope you will, I desire to extend to

you a most cordial invitation to visit me at Canton as my guest. We ought to

take active steps to spread the Theosophical truths among the people. For these

and other kindred questions we can discuss when we meet.

Awaiting an early reply and with great respect.

Yours truly,

Wu Ting Fang

Annie Besant replied on 12 July 1922:

Dear Sir & Brother,

I fear there is no chance of my visiting China, so far as I can see at present;

the T.S. Vice-President might perhaps visit the Saturn Lodge next year.

If my good fortune leads me to your Homeland, I shall gladly accept your

invitation.

With cordial good wishes

Annie Besant

Dr. Wu Ting Fang never receive the reply as he passed away on 23 June 1922.

It was indeed a loss for the Theosophical Society that Dr. Wu passed away only three years after the first lodge in China – the Saturn Lodge, of which he was active behind the scene – was formed. He gave public lectures on Theosophy in Chinese as early as 1916. In the Saturn Lodge 1920 membership register, he was listed as being attached to the U.S.A. Section. He joined The Theosophical Society in Krotona officially on 23 August 1916 although he was active and doing work for the TS earlier than that. Being a Chinese scholar highly proficient in both the English and Chinese languages and in a position of power and influence, he was pre-eminently qualified to translate Theosophical literature to spread Theosophy throughout Greater China. Then again, he was already 80 years old when he died. However, his legacy was preserved and the name he chose for The Theosophical Society was kept active until the Second World War. It has now been revived.

After his passing a letter was written on 8 July 1922 to Annie Besant to apply for a Lodge Charter for Sun Lodge which was the only truly Chinese Lodge. That was something Dr. Wu Ting Fang had wanted to do. The application written in Chinese was translated as follows:

To Dr Annie Besant

We, the undersigned Members of the Saturn Lodge of The Theosophical Society,

Shanghai, China, being desirous of forming a Chinese Lodge hereby beg to make an

application for a Charter to be granted us in the name of The Sun Lodge,

Shanghai.

We have been associated with The Saturn Lodge for a period of three years and

believe the time has now come to inaugurate our own Lodge.

Our late and venerable member, Dr. Wu Ting Fang, was particularly interested in

this matter and was in communication with us regarding making application for a

Charter up to the moment of his passing over.

We therefore consider it fitting to include his name as one of the founders – he

had already signified his acceptance of the office of President – in view of the

personal and practical interest he has always shown in and his devotion to the

cause of Theosophy in China, thus shall his name be recorded for the future

history of our Society in China.

Only Theosophy can, in our opinion, unite the three religions of China and

through the propagation of its teachings and ideals, together with the daily

practice thereof by the peoples of China, will our country again be able to take

its right place among the nations of the world.

With assurances of our complete devotion and loyalty to you and fraternal

greetings to all Brothers.

Fraternally yours,

signed. Dr. Wu Ting Fang/ Hee Wan A. / H.L. Park/ Tseng Yue Sung / Dr. Chan Git

Cho / G.F.L. Harrison/ Tong Sum Chuen / Dr. Lin Chin Hua / Lou Lum King / Kee

Chan Lun / Chan Sun Yuen / Oakland Lu

The Lodge Charter for The Sun Lodge (known in Chinese as 申江證道學會太陽會所) was issued on 8 August 1922.

The Theosophical movement in China was reorganized in 1924 by the new president of the Shanghai Lodge, Dorothy M. Arnold. Her Theosophical movement in Shanghai was supported by the Hong Kong Lodge’s founder and president, Malcolm Manuk, an Armenian born in India. He was a secretary for the Dairy Farm Company and frequently visited Sydney for business purposes. He joined the Theosophical Society as a member attached to Adyar on 3 August 1910 and remained a member until his death in 1932. It was he who had sent Wu Ting Fang’s letter to Cousins and arranged their meeting in 1920. Manuk was also active in the Theosophical network between China and Australia. Some former members of the Saturn Lodge, such as H. P. Shastri and Alexander Horne, an American Jewish Theosophist, also played active parts in the re-creation of the Chinese Theosophical movement. Horne endeavored to publish Chinese Theosophical literature, and he was in charge of the “China Publication Fund,” which was established by the Shanghai Lodge. Furthermore, Arnold supported the Chinese in reopening the Chinese Lodge under the name of Dawn Lodge in 1924; H. P. Shastri founded the “China Lodge” in 1925 with Chinese Theosophists. Under the guidance of Arnold, Theosophists in China put more emphasis on Theosophical missionary work to the Chinese. Arnold and Chinese members of the Theosophical Society established the first Theosophical school in Shanghai in 1925.

Pei Cheng Girls' School (Besant School for Girls | now Shanghai Theatre Academy Affiliated High School)

Kinson Tsiang, the president of the Theosophical Society’s Dawn Lodge in Shanghai, said: “Although, here in Shanghai, there are two or three branches, yet they have been established by foreigners. It was not until the tenth year of the Chinese Republic that a new branch, under the name of the ‘Sun’ Lodge, was organized by Dr. Wu Ting Fang, a learned Chinese, who sympathized very much with the objects; but after his death, as there was no one to hold it together, the Lodge gradually became extinct”.

In The Seventy-Fifth Anniversary Book of The Theosophical Society by Josephine Ransom we have this statement in the Year 1936:

“Mr. A. F. Knudsen was appointed Presidential Agent for East Asia. He and his wife made Shanghai their centre— ‘a better place than Hong Kong to contact the real China’. An appreciable amount of Theosophical literature had already been translated into Chinese.”

Indeed, Mr. Knudsen presented one of these translated books, Theosophy (證道學) in Chinese to Adyar on 21 January 1938. It is not known when the book was first published. The translator’s name is given in Chinese as Yuanhujinhuilian (鴛湖金慧蓮先生). This is a rather comprehensive book and the closest to a Chinese theosophical manual.

Two versions of At the Feet of the Master were found with the Chinese title Shixun (師訓). One of them has a Preface by Mr. Knudsen dated 17 April 1937. However, the translator was not named. The other version is undated but evidently an older version translated by Lin Haohua (三水林浩華).

In A Short History of The Theosophical Society in the Year 1937, the following was reported about Mr. C. Jinarājadāsa on his way back from Japan:

“On his return journey he spent a longer time in Shanghai, where he gave one public lecture and addressed the Lodge several times, and gave a lecture on Buddhism to the ‘Pure Karma Society,’ which was translated into Chinese.”

In The Seventy-Fifth Anniversary Book of The Theosophical Society in the Year 1939, we have this report:

“In Shanghai Mr. Knudsen was preparing, with the help of scholars, translations into Chinese of First Principles of Theosophy, by C. Jinarājadāsa, and The Ancient Wisdom, by Annie Besant.”

We do not know whether translations were actually carried out as Chinese translations of these books were not to be found.

In a letter dated 5 March 1937, A.F. Knudsen, then Presidential Agent, wrote to Dr. G. Srinivasa Murti, then Recording Secretary of the TS:

“Many thanks for the list of defunct

T.S. Lodges in China. It is very hard to find any trace of them here, even Miss

Dorothy Arnold has no real record of them. So far she has given me no names of

the old Chinese members except those who have definitely dropped out. Those who

do hold to Theosophy, and know no English, never knew her and would never come

to an English speaking meeting. A young man who saw my T.S. pin on my coat, told

Mr. Eiswaldt later he had seen an old Chinese gentleman who wears a similar one

on his coat. It is almost impossible to trace these ‘lost members’, but I may

put a notice, a “personal” in the Chinese papers, asking such to get in touch

with me, or the Lodge. I will try in Hankow too to reach any that may be still

interested. The movement really died with the death of Dr. Wu Ting Fang, who was

a really strong man.”

Then came World War II. In The Seventy-Fifth Anniversary Book in the Year 1944, was the ominous pronouncement:

“In Burma, Netherlands East Indies and the Philippine Islands the Society was practically extinguished by the Japanese, as were the Lodges in Shanghai (China), Hong Kong and Singapore.”

After World War II and the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution of The People's Republic of China taking place from 1966 through 1976, The Theosophical Society ceased existence in China. The Hong Kong Lodge ceased to function as soon as war hostilities started on 8 December 1941. A meeting was held on 20 December 1946 with 9 members to consider revival of the Hong Kong Lodge. They did not proceed with the revival. Hong Kong remained quiescent until an application for Lodge Charter dated 15 May 1959 was received. It was signed by Mr. K. S. Fung as President with 7 others, including Mr. K. S. Sze as Treasurer. A new Charter was issued by Adyar on 30 July 1959. No records were found of the new lodge’s subsequent activities. However, another version of At the Feet of the Master with the Chinese title of Lizugongtinglu (禮足恭聽錄) translated by Mr. Maurice Chu (朱寬) was published in Hong Kong by Mr. K. S. Fung in 1961 and reprinted by Mr K. S. Sze in 1972 in their personal capacity. Mr. K. S. Fung, proprietor of Hang Tai & Fungs Co. and Mr. K. S. Sze proprietor of K. S. Sze & Sons Co. were well-known personalities in Hong Kong. Up till then, The Theosophical Society was still referred to by the Chinese name given by Dr. Wu Ting Fang – Zhengdaoxuehui (證道學會). This book, together with the aforementioned seven, are the only eight Chinese books kept in the Adyar Library and Research Centre and are believed to be the only ones extant.

The Theosophical Society is currently not present in China. As it is verily the mission of the Society to “popularize a knowledge of theosophy”, we must not neglect China, with its population of 1.4 billion people. In this respect, under the auspices of the Indo-Pacific Federation of the Theosophical Society, a Chinese Project Team was set up in December 2011 at the Singapore Lodge to promote Theosophy to the Chinese-literate population of the world, primarily in China, and also the estimated 50 million overseas Chinese. To this end, we have developed a dedicated Chinese website www.chinesetheosophy.net as the vehicle for the dissemination of theosophical teachings. Fortunately, China has high computer literacy. Of the population of 1.411 billion, there are an estimated 1.09 billion internet users according to statistics as of 2023. This is 34.4% of all users in Asia. The work of the Chinese Project Team consists of on-going translation of theosophical literature into Chinese which is progressively posted on the website and also facilitating online forums for interactive discussions of theosophical subjects. Work has only just begun. We have uploaded images of the eight Chinese books published in the early days of the TS in China, made available by the Adyar Library and Research Centre to our Chinese website. You will find much more newly translated works in recent years. We expect to accomplish more in time to come.

And we have reverted to and shall propagate the Chinese name Zhengdaoxuehui (證道學會) composed by Dr. Wu Ting Fang as the official name for The Theosophical Society thereby preserving his legacy. After all, that name has been recognized as the official Chinese name for The Theosophical Society from 1920 until at least 1972. It is an interesting twist in history that the Chinese Project Team should be established in Singapore, the country of birth of Dr. Wu, to continue his theosophical work in China.

Compiled by

Chong Sanne (鍾山兒)

President, The Singapore Lodge Theosophical Society

Presidential Representative, East & South East Asia, The Theosophical Society

References

Ransom, Josephine, A Short History of The Theosophical Society

Jinarājadāsa, C. The Golden Book of The Theosophical Society

Ransom, Josephine, The Seventy-Fifth Anniversary Book of The Theosophical Society

Chuang, Chienhui, Theosophy across Boundaries, Chapter 4 Theosophical Movements in Modern China

The Theosophical Encyclopedia

Wikipedia

Wikipedia (Chinese)

Baidu Encyclopedia (Chinese)

Wu, Ting Fang, America Through the Spectacles of an Oriental Diplomat (in English)

Wu, Ting Fang, Information for Enquirers (Chinese translation of Annie Besant’s writings)

Wu, Ting Fang, Outline of Theosophy (Chinese)

Wu, Ting Fang, Elementary Lessons on Karma (Chinese translation of Annie Besant’s writings)

Wu, Ting Fang, Dr Wu Ting Fang’s Dialogues On Theosophy (Chinese)

TS in China, Theosophy (Chinese) (1938)

TS in China, At the Feet of the Master (Chinese) (undated)

TS in China, At the Feet of the Master (Chinese) (17 April 1937)

Chu, Maurice, At the Feet of the Master (Chinese) (1972)

Internet World Stats – www.internetworldstats.com

Theosophy in China Entry in Theosophical Encyclopedia

The first lodge in China was the Saturn Lodge in Shanghai chartered in 1920, with Mr. H. P. Shastri as President and Mr. G. F. L. Harrison as Secretary. This was apparently renamed as Shanghai Lodge, since it is so reported in the annual report of 1924. In 1922, Sun Lodge was chartered in Shanghai. The theosophical efforts in China were often pioneered by Westeners who were then living in various parts of China.

In 1923, two more lodges were chartered, the Hankow Lodge, in Hankow, and the Hongkong lodge in Hongkong (headed by M. Manuk). In 1924 Dawn Lodge was formed in Shanghai headed by Kinson Tsiang. This was composed of young people. In 1925 Blavatsky Lodge was formed also in Shanghai, headed by Dorothy Arnold. This consisted of Russians who lived in Shanghai, and the dearth of theosophical books in Russian was a problem to the group. During this time, Arnold also conducted educational work for children. The Besant School for Girls was opened in 1925. It was successful, such that by 1928, the student population had grown to 340. In 1930, it grew to 448, and many had to be refused admission. Miss Arnold had to resign as Vice President of the Lodge to focus on the school’s work.

In 1925, Edith Gray of the American Section visited the Shanghai Lodge and gave lectures on Karma and Reincarnation, which led to the formation of a Karma and Reincarnation Legion. They published Far Eastern T.S. Notes which came out every two months. Translations were made of theosophical books, such as At the Feet of the Master, Theosophy and The Riddle of Life. By 1925, theosophical centers were established in Amoy (Xiamen), Swatow (Shantou), Macao and Hoihow (Haikou), all in southern China. In Macao, a newspaper controversy on reincarnation arose lasting for an entire month, which brought reincarnation and theosophy to the attention of the masses. The newspaper exchange was subsequently printed in book form. In the same year, a lodge was organized in Tientsin (Tianjin), called the North China Lodge. The Presidential Agent for China was Mr. M. Manuk in 1928 based in China. Later, however, the theosophical activity in China was under the Presidential Agency for East Asia. The lodges were visited by C. Jinarājadāsa in 1937. During that year, the theosophists also established a Vegetarian Society in Shanghai.

During the second world war, theosophical activities in Shanghai and Hongkong ceased, and when the communists took over China in 1949, all theosophical groups ceased to function except in Hongkong, which was a British colony. The Hongkong lodge however was only intermittently active, and by the 1990s, there was no longer any theosophical meetings or activity there. Theosophical literature in Chinese were mostly written in the old classical style rather than the modern style or baihua, hence are relatively harder to read for later generation Chinese.

V.H.C.

.

Go to Overview

Visit our Chinese website 中文网站